The schoolmaster-poet William Cory wrote this restrained and moving translation of Callimachus‘s elegy to his friend Heraclitus.

They told me, Heraclitus, they told me you were dead,

They brought me bitter news to hear, and bitter tears to shed.

I wept as I remember’d how often you and I

Had tired the sun with talking and sent him down the sky.

And now that thou art lying, my dear old Carian guest,

A handful of grey ashes, long, long ago at rest,

Still are thy pleasant voices, thy nightingales, awake;

For Death, he taketh all away, but them he cannot take.

Callimachus (c. 310-260 BC)

tr. WILLIAM CORY (1823-1892)

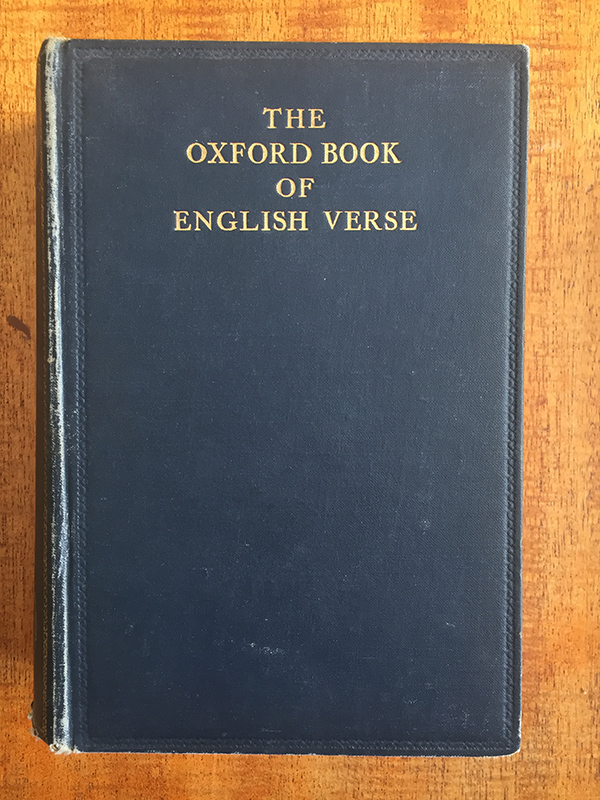

It is an astonishing feat of translation. Arthur Quiller-Couch considered it worthy of inclusion in his 1919 Oxford Book of English Verse as a work of English poetry in its own right.

Not long ago, Cory’s translation was well-known to every schoolchild.

John Ireland and Charles Villiers Stanford composed exquisite settings of the poem.

A few brief notes relating to Heraclitus

- Who was William Cory?

- Who was Callimachus?

- Who was Heraclitus?

- Callimachus’s original poem in Greek.

- A painfully literal translation that rusty students of Greek (like me) might find helpful in refreshing their memories.

- A transliteration of the Greek.

- A little about Greek poetry and meter

1. Who was William Cory?

William Johnson was a schoolmaster at Eton, “the most brilliant Eton tutor of his day” (GW Prothero). Arthur Balfour, who became Prime Minister, was one of his pupils.

At the age of 49 he was dismissed in opaque circumstances.

He changed his name to Cory, his paternal grandmother’s maiden name, and retired to Malta, eventually returning to Hampstead for the last ten years of his life.

2. Who was Callimachus?

Callimachus of Cyrene (Libya) was a scholar-poet at the great Library of Alexandria during the first half of the third century BC.

His work included cataloguing the entire collection of the Library (his 120-volume Pinakes). He laid the foundation of future scholarship.

He died in Alexandria in 260 BC. C

Callimachus wrote poetry in the new “Hellenistic” style, rebelling against the old epics.

He conducted a lengthy feud with his student Apollonius of Rhodes, who wrote epic, for this reason, and possibly (probably not) because Apollonius was promoted to Chief Librarian, a position that eluded Callimachus.

It was Callimachus who said μέγα βιβλίον μέγα κακόν (mega biblion mega kakon), “big book, big problem”, a view perhaps shared by many students in the 2,280 years since his death.

3. Who was Heraclitus?

The Heraclitus referred to in this poem is not the pre-Socratic philosopher (who died two centuries earlier), but a poet and friend of Callimachus.

He wrote a volume of poetry called Aēdones (‘Nightingales’), referred to in the poem.

Heraclitus lived in Halicarnassus in SW Anatolia, part of Caria (hence Cory’s metrically-convenient translation).

Halicarnassus, with its spectacular views over the Ceramic Gulf, was the home of one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World: the Tomb of Mausolus, or the Mausoleum.

Ancient Halicarnassus is now modern-day Bodrum in Turkey – still a beautiful place.

We have no idea whether Callimachus ever visited Halicarnassus: there is no solid evidence one way or the other.

4. Callimachus’s original poem in Greek

Εἰπέ τις, Ἡράκλειτε, τεὸν μόρον ἐς δέ με δάκρυ

ἤγαγεν ἐμνήσθην δ᾿ ὁσσάκις ἀμφότεροι

ἠέλιον λέσχῃ κατεδύσαμεν. ἀλλὰ σὺ μέν που,

ξεῖν᾿ Ἁλικαρνησεῦ, τετράπαλαι σποδιή,

αἱ δὲ τεαὶ ζώουσιν ἀηδόνες, ᾗσιν ὁ πάντων

ἁρπακτὴς Ἀίδης οὐκ ἐπὶ χεῖρα βαλεῖ.

Callimachus XXXIV G-P, A.P. 7.80, Diog. Laert. ix. 17

5. A painfully literal translation for rusty students of Greek

Someone (τις) told (Εἰπέ) me, Heraclitus, of your death (μόρον) and brought (ἤγαγεν) me tears (δάκρυ). I remembered (ἐμνήσθην) how often (ὁσσάκις) we both (ἀμφότεροι) in conversation (λέσχῃ) brought down (κατεδύσαμεν) the sun (ἠέλιον).

But you, now, I suppose (που), Halicarnassian friend (ξεῖν᾿ = ξένε), are ash-grey (σποδιή) long ago (τετράπαλαι); but your nightingales (ἀηδόνες) are alive (ζώουσιν), upon which (ᾗσιν) that robber (ἁρπακτὴς) of all things (πάντων), Hades, shall not (οὐκ) lay (βαλεῖ ) his hand (χεῖρα) .

tr. Andrew Gadsden

6. A transliteration of the Greek

Eipe tis, Herakleite, teon moron es de me dakru

Egagen emnesthen d’ hosakis amfoteroi

Heelion leschei katedusamen. Alla su men pou,

Xein Halikarneseu, tetrapalai spodie

hai de teai zo-ousin aedones, hesin ho panton

harpaktes Haides ouk epi cheira balei

7. Greek poetry and meter

Ancient Greek and Latin poetry does not normally rhyme, but is written in a rhythm or meter which follows clear rules.

This epigram (Epigram 2) is written in Elegaic Couplets, pairs of lines where the first has six feet (a hexameter) and the second five (a pentameter), with a break (caesura) in the middle.

You can write out the scheme as follows:

– U | – U | – U | – U | – u u | – –

– U | – U | – || – u u | – u u | –

– = long syllable

u = short syllable

U = one long OR two shorts

Read the following nonsense rhyme to get a feel for the rhythm:

Down in a | deep dark | dell sat an | old pig | munching a | beanstalk.

Out of his | mouth came | forth || yesterday’s | dinner and | tea.

Coleridge gave a more elegaic example:

In the hexameter rises the fountain’s silvery column,

In the pentameter aye falling in melody back.